What is Andragogy?

The term "Andragogy" as defined by American practitioner and theorist, Dr. Malcolm Knowles (1980), is "the art and science of helping adults learn" (p. 43). The term was conceived in 1833 by a German elementary school teacher, Alexander Kapp, to explain Plato's educational model to his students. Thereafter, andragogy as a label was used infrequently until 1926, when Eduard C. Lindeman adopted the moniker from the Germans and brought it to America through his writings, describing it as a "key method for teaching adults" (Henschke, 2011, p.34). Knowles then discovered the term in 1966 from Yugoslavian adult educator, Dusan Savicevic, and in 1968 began to use it in articles about adult leadership and education. From here on, andragogy developed both in meaning and scope to become what we know today as the educational model for the adult learner.

Six Assumptions of Andragogy?

Knowles, along with other educators, researched, tested, expanded, and finally theorized the concept of andragogy to include six assumtpions about adult learning. These assumptions, as outlined by Knowles, Holton and Swanson (1998) serve as a model of how adult learners differentiate themselves from children learners, and are explained as follows:

1) The Learner's Need to Know: Adults have the need to justify why they are to learn new knowledge. They need to understand the benefits of learning new information versus the negatives of not ascertaining this new knowledge. Ultimately, they need to have a reason to learn. Instructors, in this capacity, need to become facilitators who make their students aware of their need to know new content.

2) The Learner's Self-Concept: Knowles, Holton and Swanson (1998) asserted that "adults resent and resist situations in which they feel others are imposing their wills on them" (p. 65). Psychologically, as adults mature they become more self-aware, more independent and realize they become the decision makers of what they learn and how they learn. No longer is it up to the educator to dictate specifically what will be taught, how and when it will be learned.

3) The Role of Learner's Experience: Adults, by virtue of living longer than children, have a wealth of experience and knowledge that cannot and should not be considered irrelevant in the learning experience. Adults, in the learning process, want their previous knowledge to be acknowledged and in fact used as they acquire new information or learn new tasks. Adult educators, keenly aware of their students' resources in this regard, use "experiential techniques such as, simulation exercises, problem solving activities, case methods, laboratory methods, and group discussions" in their instruction (Ozuah, 2005, p. 84).

4) Learner's Readiness to Learn: Knowles contended adults are ready to learn when "they experience a need to learn it in order to cope more satisfyingly with real-life tasks or problems" (1980, p. 44). Therefore, when reasons for learning are based on employing the new knowledge or training in real-life settings, adults gain this willingness to learn and are thereby "ready" to learn the subject at hand.

5) Learner's Orientation to Learning: As cited by Ozuah in his commentary on adult learning theory, the "adult's orientation to learning is problem-centered, task-centered, or life-centered" (2005, p. 84). Adults, then, want to ensure what they learn will apply in a real-world context. Whether it be to perform a new task at work or solve a problem at home, adults want to know that what they are learning will eventually help them in their daily lives.

6) Learner's Motivation to Learn: The final assumption claims adult learners are motivated to learn based more on internal goals that are driven to increase self-respect and pride. Adults, in their quest to improve as people, as workers, or in their quality of life, by nature will never stop growing and developing, hence their motivation to learn.

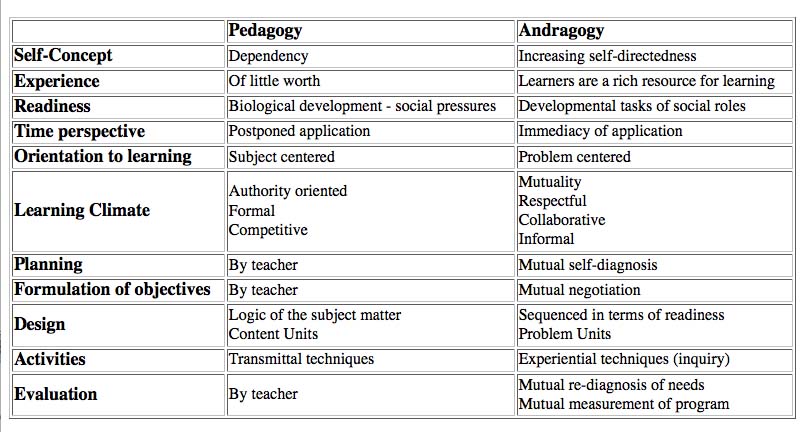

The table below, created from studies and research in the field, describes the ideal environment and

principles for adult learning (Ozuah, 2005, p. 86).

Andragogy vs Pedagogy

Before comparing andragogy from pedagogy, it is important to first define pedagogy. As cited by Dr. Philip Ozuah (2005) "pedagogy is derived from two words, paid meaning 'child' and agogus meaning 'leader of.' Thus, it literally means the art and science of teaching children" (p. 83). Foundational assumptions of pedagogy base the learner as a dependent, who does not know what they need to learn. In addition, learning is both subject and teacher-centered, and learner's motivation is based on rewards and punishment.

Andragogy's paradigm, on the other hand, greatly differes that of pedagogy. The term comes from the Greek word andros which means "adult man" and ago, "I guide" (Zmeyov, 1998, p.104). As ago—I guide—insinuates the adult, as a more self-directed learner, thrives in an educational setting which allows for more autonomy. Instruction may employ different learning theories, but many use case studies involving collaboration with colleagues to solve problems based on real-life situations. The adult learner, rich in experiences, can also tap into their reservoir of prior knowledge to gain new knowledge and are more motivated to learn than a child, when learning content will benefit and/or enhance their "professional and personal growth"(Ozuah, 2005, p. 86). This, in effect, is the adult's reward for learning.

The Table below outlines the differences between "Pedagogy" and "Andragogy"

Watch the YouTube video: Pedagogy vs Andragogy (Adult Learning) which presents a nice lecture as outlined above.

Andragogy and Technology

With the progressive evolution of information technology in the past century, coupled with the revolutionary advancements of the internet as a means of communicating and acquiring information, it is only natural that technology would assume a pivotal role in the field of adult education. Yet, precisely what role does technology perform in the realm of andragogy? Is it merely used as a vehicle for delivering content online or does technology play a more active role in how adults learn new concepts and skills.

Dependent upon how it is used by either the instructor or learner, technology can assume varying roles in the process of adult learning. It can be used in courseware development, presentation of content, and/or delivery of instruction. It can play both a passive and active role. However, technology can realize its maximum potential, when its design is centered on how the adult learner processes information and what incites them to learn. As explained by Dolores Fidishun, "Introducing technology into the curriculum means more than just 'making it work.' The principles of adult learning theory can be used in the design of technology-based instruction to make it more effective" (2009, p. 1). Therefore, the six assumptions of andragogy help form a basis to build upon when integrating technology with adult education (Fidishun, 2009).

Key factors which facilitate the fusion of andragogy and technology are:

1) Instructional content must have relevance to the adult learner. Content presented may require the adult to use the latest software or technological tool, but courseware needs to have meaning for the learner if it is to be studied.

2) Because adult learners are independent and motivated to take on a course of study for professional advancement or personal development, technology-based lessons should be easily modified to meet a learner's interest or need. It's in this domain where adult learning becomes more self-directed.

3) Technology-based courses can take on various forms in its delivery of instruction from video and/or audio presentations, to podcasts, wikis, blogs, synchronous and asynchrounous learning environments, and numerous other formats. This variety and choice in instruction can cater to differing learning styles of adults and should facilitate the learning process.

4) In addition to the varying ways adults learn, considerations can also be made as to when and where an adult learns. In today's global environment, adults have schedules that may change day to day, minute to minute. What better format is there than technology to deliver instruction twenty-four hours a day / seven days a week, if needed. Adult learners with their ever-changing schedules can participate in an asynchronous course at midnight while away on a business trip in another continent. Due to the emergence of technology, time and place are no longer definitive factors on when education can take place, which is especially beneficial for the adult learner.

5) Finally, "technology-based instruction will be more effective if it uses real-life examples or situations that adult learners may encounter in their life or on the job" (Fidishun, 2009, p.3). Lessons should include group based activities and problem-solving exercises, that give the adult learner the opportunity to collaborate with others and apply prior knowledge or learned skill sets. In this way, the adult learner can better relate and contribute to their program of study.

Conclusion

Andragogy has developed from a term to an educational model to finally an established field of education. From Knowles' definition of andragogy as representing "the art and science of helping adults learn" (1980, p. 43), it has evolved and matured into representing an alternative to learning that is driven by the learner, not the instructor, that is problem-centered, not subject-centered, and involves continual application of past experiences and collaboration with others. With technology and research as its partner, andragogy will continue to flourish as a viable academic discipline for the present and future of adult education.

Watch the YouTube video: Andragogy (Adult Learning) which presents a nice synopsis of its roots and the six assumptions of adult learners as outlined above.

Additional recommended websites to visit on andragogy are:

http://www.lindenwood.edu/education/andragogy.cfm

http://frank.mtsu.edu/~itconf/proceed00/fidishun.htm

http://www2.selu.edu/Academics/Faculty/nadams/etec630&665/Knowles.html

References

Conner, M. L. (1997-2004). Andragogy and Pedagogy. Ageless Learner. Retrieved from http://agelesslearner.com/intros/andragogy.html

Downing, Carla A. (2010). The college network -- The importance of pedagogy. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17T1h0gf3IM

Fidishun, Dolores (2000, April). Andragogy and Technology: Integrating Adult Learning Theory As We Teach With Technology.

Penn State Great Valley School of Graduate Professional Studies. Retrieved from http://frank.mtsu.edu/~itconf/proceed00/fidishun.htm

Finlay, Janet (2010). Andragogy (Adult Learning). Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLoPiHUZbEw

Henschke John A., (Winter 2011). Considerations regarding the future of andragogy. Adult Learning 22, no. 1 : 34-37.

Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Cambridge, Englewood Cliffs.

Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E.F., and Swanson, R. A. (1998). The Adult Learner. Butterworth:Heinemann, Woburn, MA.

Merriam, Sharan B. (2001, Spring). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory.

New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, no. 89.

Ozuah, Philip O. (2005, March). First, there was pedagogy and then came andragogy. Einstein Journal of Biology & Medicine 21,

no. 2: 83-87.

Smith, M. K. (2002). Malcolm Knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogy, the encyclopedia of informal education,

Retrieved from http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-knowl.htm

Smith, M. K. (1997, 2004). Eduard Lindeman and the meaning of adult education, the encyclopaedia of informal education,

Retrieved from http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-lind.htm.

Zmeyov, Serguey I. (1998, January). Andragogy: Origins, developments and trends. Springer science & business media B.V.